How US Export Controls Have (and Haven't) Curbed Chinese AI

Six years of export restrictions have given the U.S. a commanding lead in key dimensions of the AI competition — but it’s uncertain if the impact of these controls will persist.

Chris Miller — July 8, 2025

For over half a decade, the United States has imposed significant semiconductor export controls on China, aiming to slow China’s chip industry and to retain US leadership in the computing capabilities that undergird AI advances. Have these controls achieved their goals? Have the assumptions driving them been confirmed or undermined by the rapid evolution of the chip industry and AI capabilities?

Three factors for assessing chip export controls. We can now draw preliminary conclusions by assessing three factors: China’s domestic chipmaking capability, the sophistication of its AI models, and its market share in providing AI infrastructure.

Initial evidence shows that controls have succeeded in several important ways, though not all. Restrictions on chipmaking tool sales have significantly slowed the growth of China’s chipmaking capability. However, restrictions on the export of AI chips to China, while creating challenges, have not prevented Chinese labs from producing highly competitive models (though they may make it harder for China to deploy their models at scale). Controls have severely limited China’s share of the global AI infrastructure market, because, lacking competitive hardware, Chinese cloud computing firms have been unable to establish much, if any, AI infrastructure outside of China.

The Current Chip Export Control Regime

To understand these effects, it’s useful to briefly review the structure and evolution of the export control regime.

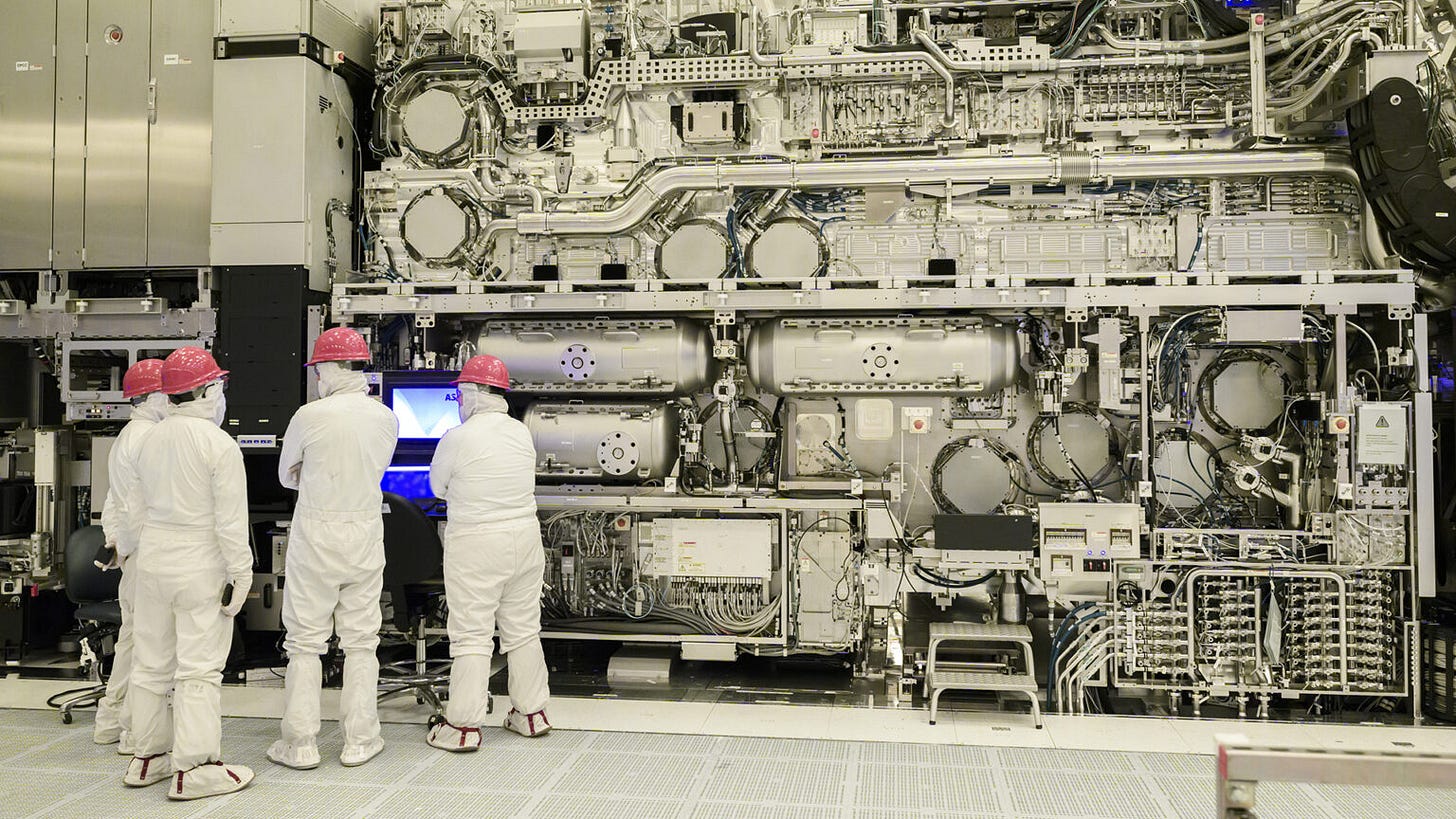

Escalated export controls began by prohibiting the sale of equipment essential for chip manufacturing. The US has had export controls on semiconductors and chipmaking equipment for decades, but the current phase of escalated controls on China began in 2018, when the US started encouraging the Netherlands to restrict sales of the most advanced extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography tools to China’s leading chipmaker, the partially state-owned Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC).

EUVs are produced by a single company — the Netherlands’ ASML — and cost over $100 million each. Only a handful of companies have acquired these tools. Barring US pressure and the Dutch decision to block the sale, China would have acquired its first tool in 2019, and it would likely have acquired many more since then.

The US strategy for containing China has shifted toward an explicit focus on AI. The blocked EUV sale was part of a US campaign to keep China technologically behind the US. This campaign ratcheted up in October 2022, shifting from broad containment to an explicit focus on constraining China’s AI industry. That shift reflected a growing awareness within the US government of how AI progress increasingly depended on access to the computational (“compute”) hardware required to train AI models. US government officials had been closely tracking trends in AI, including the central role of “scaling laws” — the prediction, based on empirical observations, that AI capabilities are improved by larger training runs. If these scaling laws held, access to the most advanced semiconductors would be an important precondition for developing and deploying AI at scale.

The October 2022 controls thus sought to limit China’s access to chipmaking tools and AI chips themselves, which at the time were made mostly by US firms like Nvidia. Shortly after, Japan and the Netherlands — the two other countries that produce advanced chipmaking tools — imposed controls similar to those US export restrictions. Taiwan and South Korea, which have high-end chip-manufacturing capabilities, have also enforced control rules (with loopholes, discussed below). The US has since tightened controls even further, through several rounds of new restrictions on the transfer of tools and chips to China.

The Impact on China’s Chip Industry

To understand the impact of these restrictions on China’s chipmaking capabilities, we have to consider the counterfactual: how much progress would China have made in the absence of export controls?

SMIC could have become the second-largest producer of advanced AI chips. We know that SMIC would have acquired at least one EUV tool in 2019, had it not been blocked from doing so. Had that sale gone through, SMIC would probably have bought many more. China’s government, in turn, would likely have moved to support the entry of SMIC into the industry by ramping up public investment. In this scenario, SMIC would likely have become a far larger producer of advanced AI chips than South Korea’s Samsung, America’s Intel, and any other firm, except for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

Want to contribute to the conversation? Pitch your piece.

The emergence of SMIC as a major player in advanced chip production would likely have led Western firms to invest less, on the rational conclusion that SMIC would drive down the profitability of competing investments. This same dynamic has played out in the market for less-advanced foundational semiconductors in recent years, where China’s access to relevant chipmaking tools has not been restricted.

Export controls have had knock-on effects on other Chinese technological capabilities. Access to high-end tools would also have supercharged China’s capabilities to produce high-bandwidth memory chips, which must be paired with AI processors for efficient training and inference: the process of running a trained model to generate outputs in real-world applications. While China’s leading firm in this sphere, ChangXin Memory Technologies (CXMT), has faced somewhat weaker restrictions than SMIC, which produces processors for Huawei, it has still been banned from acquiring EUV tools and other types of advanced tools that are useful in efficient memory chip manufacturing. Today, most of the high-bandwidth memory (HBM) chips paired with Huawei’s AI processors are either purchased or smuggled from abroad. Better access to advanced tools would have improved CXMT’s pathway to producing cutting-edge HBM.

Export controls have made China a marginal producer of AI chips. Setting aside the counterfactual, let's consider the actual impact of export controls since 2018: restricted access to chipmaking tools has severely hindered China’s industry. The result is that China remains a marginal producer of AI chips. According to recent congressional testimony by US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, Huawei will produce only 200,000 AI chips in 2025. By contrast, in 2024, China reportedly legally imported around 1 million chips that Nvidia had downgraded specifically for the Chinese market.

Chinese companies must resort to smuggling. This inability to produce large volumes of advanced chips domestically explains why Huawei and other Chinese companies have resorted to large-scale smuggling. While many of the specific smuggling schemes reported in the media involve relatively small numbers of chips, the prevalence of such anecdotes suggests that the volume of chips entering China via this route is significant. What’s more, Huawei worked with a shell company that, until 2024, illegally procured over 2 million chips from TSMC.

In other words, Huawei’s largest supplier of chips today is not China’s domestic manufacturing capabilities but, instead, a shell company illegally sourcing chips from Taiwan. This is a dramatically different status quo from the counterfactual scenario, in which SMIC would be a close second to TSMC in advanced chip manufacturing.

China is unlikely to catch up. For now, therefore, China’s AI chip production capacity is far behind the West’s. Its evolution relative to that of Western countries will depend on Chinese firms’ ability to make do with second-best equipment; the level of future US controls, which could be tightened or loosened; and the rate of technological advance in the Western supply chain.

Most estimates suggest that China is likely to increase its production capacity over the next few years. (Of course, TSMC will increase its capacity and develop even more capable manufacturing techniques, too.)

The Impact on AI Model Development in China

Chinese models have advanced despite export controls. Chip export controls have clearly had a significant negative impact on China’s ability to produce advanced chips. But have those hardware limitations hindered the capability of Chinese models? Perhaps surprisingly, the answer is: not really.

Chinese firms like Alibaba and DeepSeek have produced impressive large language models that score highly on established benchmarks for assessing model quality. Other firms, like ByteDance (which owns TikTok), focus on training internal models to recommend videos that are more addictive; by all accounts, ByteDance has done this very effectively.

It is true, of course, that Chinese entrepreneurs in the AI space often talk about the problems that AI chip export controls cause them. Liang Wenfeng, founder of DeepSeek, has publicly said on multiple occasions that his greatest single challenge is accessing chips. In a 2024 interview, he said, “Money has never been the problem for us; bans on shipments of advanced chips are the problem.”

But, despite this frustration, the technical benchmarks suggest that China’s AI models do not have a significant capability gap compared with US-produced models. In some ways, they have innovated to get around the limitations of not having high-end chips.

It could be the case that, over the next year or two, the chip access gap between US and Chinese firms will grow. US firms will build far larger clusters and will therefore be able to train significantly better AI systems. However, the trend of the last three years suggests the opposite: that, according to benchmarks, US and Chinese model capabilities are fairly evenly matched.

Export controls may have limited China’s ability to deploy AI. While chip restrictions haven’t significantly limited China’s ability to train cutting-edge models, they may have impacted Chinese firms’ ability to deploy their models at scale. After the release of its R1 model earlier this year, DeepSeek had to restrict access to its API, presumably because it couldn’t provide enough inference compute to meet user demand. That interpretation is supported by remarks from Tencent Cloud senior executive Wang Qi, who earlier this year suggested that deficits of advanced chips could slow AI adoption by limiting inference availability or driving up costs.

Thus far, however, it isn’t clear that chip deficits are delaying AI uptake in China. Puzzlingly, utilization in many of China’s data centers appears to be relatively low, with media reports suggesting that up to 80% of China’s AI chips may be unused. Many of China's medium-sized data centers appear to lack the stability to serve AI models at scale. This dynamic may be driven in part by heavy investment from state-owned telecoms and other state-owned firms, which have often managed these facilities very poorly.

Export controls may have driven Chinese firms to buy chips they didn’t need. Another intriguing possibility is that the inefficiency of Chinese data centers has been exacerbated by chip export controls. If these controls signaled to China’s leadership that AI data center capacity was important — and if that conclusion signaled to state-owned firms that they should buy AI chips — it is possible that the controls have contributed to low utilization rates by encouraging less capable Chinese firms to buy chips for political rather than market reasons. If so, this would be a counterintuitive mechanism for chip export controls to have had an impact — though evidence for this is weak.

For now, despite some unanswered questions around uptake, we must conclude that chip export controls have not seriously slowed improvements in Chinese model quality.

The Impact on China’s Ability to Provide AI Infrastructure

The last dimension along which to examine the impact of export controls is China’s ability to provide AI infrastructure to the rest of the world: that is, the chips and servers inside AI data centers. Several factors have made US firms — primarily Nvidia — the default global provider of high-end chips around the world, including in China. The quality of the company’s chips and the depth of its software ecosystem are key factors contributing to its strong market position. But export controls have also shaped the market.

Chinese companies remain dependent on US AI chips. Restrictions on the sale of chipmaking equipment have done more than drastically limit China’s domestic chipmaking capabilities. They have also helped to guarantee that, because Chinese alternatives are not available at scale, Chinese firms still want to buy large numbers of US chips (such as, until recently, H20s). Had SMIC been able to buy advanced tools and ramp up its production, it might have been able to meet Chinese tech firms’ chip demand by producing Huawei’s Ascend GPUs. Today, it cannot produce at the scale required.

Export controls have significantly impacted China’s influence abroad. This dynamic has been even more pronounced outside of China. The limits on Huawei’s ability to source AI chips have made it a negligible player in providing AI cloud computing capabilities outside of China. Today, there is just one data point — an announced deal to deploy 3,000 Ascend GPUs in Malaysia that was later retracted by the Malaysian government. Beyond that, global AI infrastructure outside China is overwhelmingly built on Western chips — a significant limit on Chinese power.

Implications for the Future of AI and US-China Relations

Half a decade of intensified export controls has left China with lopsided areas of agency: it has developed AI models whose capabilities rival those of US firms, but its inability to match US chipmaking capabilities has left it more reliant on American hardware to train and deploy these models — even domestically. It has especially limited China’s ability to deploy AI infrastructure abroad.

Several key uncertainties will shape the future impact of these controls.

Scaling domestic chip production. The most important uncertainty is how quickly China can scale up domestic chip production. China is trying to improve its manufacturing capabilities, but it’s unclear how quickly progress can be made. While US export controls still allow the shipment of certain foreign tools and materials to the Chinese fabs that make AI chips for Huawei, these allowances could be curtailed.

Sustaining chip smuggling. The second uncertainty is whether China can smuggle chips in large enough quantities to meet its demand. If Huawei can smuggle millions of chips, increasing domestic production becomes less important. So far, US export controls have been enforced much less effectively than most observers expected. Still, sustained smuggling of millions of chips presents serious logistical challenges. In addition to smuggling chips, Chinese firms can also try to illegally access US cloud services to acquire the compute they need. Here, too, export controls may be surprisingly leaky.

Scaling laws. The third uncertainty is how scaling laws will evolve. The past year has seen a clear shift in frontier model development, away from emphasizing pre-training and toward inference. This shift reflects the rise of reasoning models that perform more complex tasks during user interactions. If this trend holds, Chinese firms could continue to develop cutting-edge models but struggle to deploy them at scale.

Commercial application vs. maximum capabilities. Finally, a fourth uncertainty: will the economic impact of AI stem more from expanding its commercial applications or from maximizing its model capabilities? If adoption and productivity gains are driven primarily by domain-specific AI products, scaling compute to push the ceiling of AI capabilities may matter less than some think. China is probably better positioned in a world with higher returns to domain-specific tools, because deploying these may require less compute than developing general-purpose tools.

Export Controls Have Given the US a Commanding Lead in AI

Access to advanced chips will remain critical. Current trends suggest that access to advanced AI chips will be a critical factor in shaping the future of AI. The past six years of export controls on chips and chipmaking equipment have given the US a commanding position in AI hardware globally.

There is no serious challenge to the US. For now, there is no serious Chinese alternative providing AI infrastructure to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, or other regions. Even China is still importing US AI chips. This control of essential hardware gives Washington outsized leverage in shaping a technology that will define the future.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

Chris Miller is author of Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology.

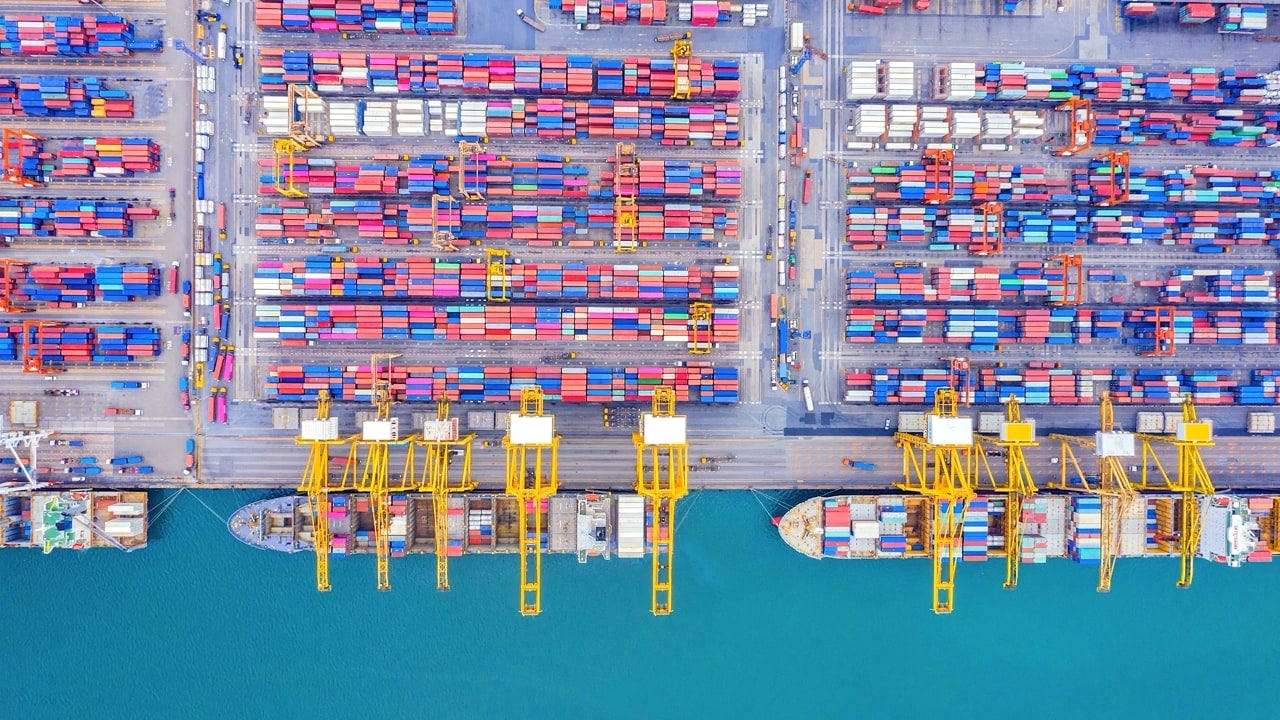

Cover image: iStock